Over the years, you’ve probably heard lots of people talk about how digital is saving trees. On the flip side, you’ve also probably found lots of articles proclaiming that the digital economy is threatening the planet.

Who’s right? To be honest, both sides have valid points, but like many things, it’s complicated. So let me take a stab at clearing the muddy waters surrounding this debate. But first, some inspiration…

“The earth is becoming too small for us. Our physical resources are being drained at an alarming rate. Mankind has presented our planet with the disastrous gifts of climate change, pollution, rising temperatures, reduction of the polar ice caps, deforestation, and decimation of animal species.

We have a role to play in making sure [school] children have not just the opportunity, but the wish to engage fully with the study of science at an early level so that they can go on to fulfill their potential and create a better world for the whole human race. I believe the future of learning and education is the internet.

People can answer back and interact. In a way, the internet connects us all together, like the neurons in a giant brain. With such an IQ, what cannot we be capable of?”

Prof. Stephen Hawking (1942-2018)

Cosmologist, theoretical physicist, and best-selling author

Brief Answers to the Big Questions

The internet is a double-edged sword

I’m writing this article in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and I’m reminded about how fortunate we are to have technology that gives us instant access to the information we need to educate ourselves and respond appropriately to this global crisis.

Without the internet, many of us couldn’t work safely from home and connect over products like Zoom with our colleagues and customers. Without the internet, we’d be at risk both physically and financially in these uncertain times.

Yes, the internet is fantastic, but it’s far from perfect. There are pros and cons to it like there are with everything in life. Here’s a list off the top of my head, but it’s not exhaustive. I’m sure you could add many more.

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

Gives people instant access to a massive amount of information, most of which is free |

Privacy risks, misinformation, copyright infringements, and inappropriate content are on the rise. |

|

Allows us to connect, communicate, collaborate globally, and share ideas and information with others in real-time, anytime |

Can lead to over-dependency on technology and information overload/content fatigue |

|

Improves efficiencies and productivity — at work, at school, when we shop, do research or banking — freeing up more time for other activities |

May become addictive and increase loneliness and social isolation |

|

Helps turn strangers into friends |

Infiltrated by cybercriminals, internet trolls, bullies, and stalkers |

|

Offers many new business opportunities |

Ripe with unwanted advertising and email spam |

|

Democratic in most countries |

Can spread propaganda |

|

Smarter homes, devices, and cars |

Uses a lot of electricity, prone to hacking |

So assuming we all agree on all the amazing things the internet has brought us, let’s focus on its impact on the planet from a Greenhouse Gas (GHG) perspective.

There are facts, and then there are factoids

Facts are funny things because they’re often not immutable over time and space. This is particularly true in technology, where what was reality yesterday is proven obsolete tomorrow. The ever-changing landscape of facts and factoids is why I try very hard to work with, and link to, the latest information on the topic I’m writing about – especially when it’s about technology. Unfortunately, not everyone does that.

Earlier, I referenced an article that said the digital economy was threatening our planet. It was written in December 2019 and had a very alarming and compelling introduction – until you looked under the hood.

All the hyperlinks in the second paragraph that substantiated the author’s bold statement were from 2013 and 2015. I’m not suggesting that the article was written to deliberately misinform, but with technological advances still growing exponentially, I would argue that 4- and 6-year-old data just doesn’t reflect 2019 reality.

Let’s start with rare earth metals. Yes, smartphones use them, as do electric cars, solar panels, wind turbines, catalytic converters, rechargeable batteries, magnets, and fluorescent lighting, to name just a few others.

But the author failed to mention that Apple is now using 100% recycled rare earth metals in its Taptic Engine — a key component in the new iPhones that will “avoid mining more than 280,000 tons of aluminum-bearing bauxite and more than 34,000 tons of tin ore over the next year.”

Not all phones use recycled metals yet. Part of the problem is that, although lithium batteries used in smartphones and electric cars can be recycled, only 5% of them are, and current processes for doing that are energy-intensive. It’s time for battery researchers and manufacturers to start focusing on improving lithium battery recyclability and help find even more sustainable ways to produce our favorite gadgets.

When it comes to how coal is fueling cloud computing, data centers, AI, and cryptocurrencies, the author chose to reference a 2013 report “sponsored” by the American Mining Association. A quick search would have unearthed a far more relevant 2019 article on how technology is evolving and leading to “low-cost, abundant energy.”

It’s hard to know what data to trust

Back in July 2019, a report from The Shift Project went viral because of this statement, “Watching a half-hour [Netflix] show would lead to emissions of 1.6 kg of carbon dioxide equivalent,” said Maxime Efoui-Hess of French think tank The Shift Project. “That’s equivalent to driving 3.9 miles (6.28 km).”

Not surprisingly, it sounded a bit off. So the BBC contacted energy and resources expert Jonathan Koomey — a Consulting Professor at Stanford University, known for identifying a long-term trend in energy-efficiency of computing known as Koomey’s law. To separate fact from fiction, the BBC interviewed Koomey in its January 2020, More or Less podcast titled “Netflix and Chill.”

Long story short: Prof. Koomey quickly debunked The Shift Project’s data. Streaming half an hour of Netflix video does not emit 1.6 kg of CO2e, it emits less than 20 grams, “probably much less.”

Koomey was very gracious and said he believed The Shift Project just made a mistake. But he did caution that not all factoids presented as facts are as innocent.

But enough about hype and scare tactics; let’s talk facts based on today’s science.

Internet demand and energy use

A decade ago, the internet was big, but today it is massive, and growing at an unprecedented rate.

Conventional wisdom tells us that as demands for data center services grow, so too should their use of energy. Given the internet’s exponential growth over the past decade, it’s no wonder people were panicking about the future back in 2010.

“If the 2010s were the decade when businesses started to realize the dangers of climate change and the impact it could have on their operations, the 2020s must be the decade when they act to dramatically reduce the emissions that cause it.”

Mike Scott

The 2020 Global 100 Progress Report

Corporate Knights

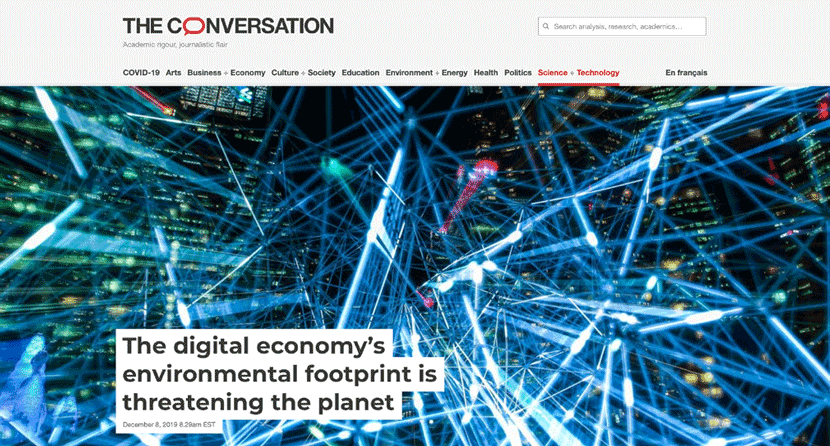

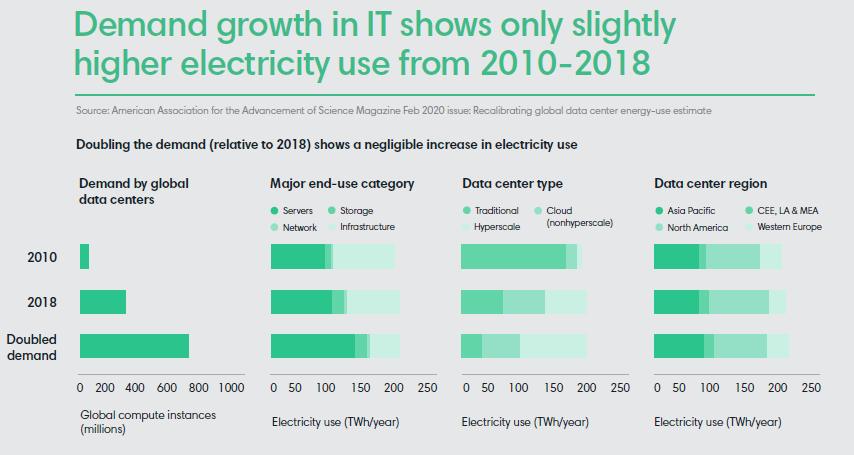

But thankfully, over the last decade, the data center technology landscape has changed dramatically. According to, Recalibrating global data center energy-use estimates, published in the February 2020 issue of the American Association for Advancement of Science Magazine, energy efficiency improvements to internet devices and cooling systems have been keeping energy use in check.

Between 2010 and 2018, global data center workloads increased more than 600%, data center IP traffic rose more than tenfold, and data center storage capacity grew by a factor of ~25.

But, what’s exciting and surprising is that electricity use over those eight years dropped by 400%, mostly due to processor efficiency improvements and reductions in idle power.

For the last four years, the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory has been publishing energy trend analyses of servers, storage devices, and network devices typically used within data centers.

They found that from 2010 to 2018, although global data center computing output increased by 600%, their energy use only increased by 6%. Even doubling the demand, relative to 2018, only showed negligible increases in electricity use.

So, the picture isn’t quite as dire as some predicted ten years ago, but that doesn’t mean the IT industry, data center operators, and policy-makers can rest on their laurels. Diligent efforts must continue to be made to manage future high energy demand growth when the current efficiency resources are tapped out.

Comparing clouds

Late in 2019, WIRED published its analysis on who had the greenest cloud between Google, Microsoft, and Amazon. It was fascinating and worth a read if you have the time. All three companies have pros and cons, as one would expect.

|

WIRED’s Rating of Cloud Providers |

Amazon |

Microsoft |

|

|

Overall Greenness |

C- |

B |

B+ |

|

Energy Efficiency |

B |

A |

A+ |

|

Transparency |

F |

A |

A+ |

|

Technological Innovation |

Unknown |

A+ |

A+ |

|

Total Renewable Energy Portfolio |

1.6 GW |

1.9 GW |

5.5 GW |

Amazon is the world’s largest cloud computing provider, owning over a third of the market. But due to accusations of it abandoning its commitment to use 100% renewable energy by Greenpeace in 2019, and its lack of transparency in its sustainability reporting, Amazon’s reputation took a significant hit in WIRED’s analysis.

Google’s internet and data services parent, Alphabet, was ranked number 62 in the top 100 most sustainable companies in the world in 2019 by Corporate Knights, and received a B+ rating in overall greenness by WIRED. Microsoft received a B rating in the latter, but didn’t making it to the top 100 list by Corporate Knights. Honestly, I expected to see a higher ranking for Microsoft, given its commitment to be carbon negative by 2030.

Perhaps Google’s and Microsoft’s less than “A” ratings are partly due to their courtship of the oil and gas industries. Chevron, Schlumberger, Equinor, and Repsol, to name a few, have contracted billons of dollars with Google and Microsoft – deals with “dirty energy” that could rub sustainability folks the wrong way. Or perhaps they rely too heavily on Renewal Energy Certificates (RECs).

Using RECs to beef up a company’s renewable energy portfolio is a widespread practice across most industries. Because businesses don’t know the origin of their electricity or how it’s generated, RECs play a key role in the accounting, tracking, and assigning ownership to renewable electricity generation and use. i.e., RECs allow companies to purchase credits so they can legally claim that the electricity they use comes from a renewable resource even though they’re still connected to grids that use fossil fuels.

Let’s talk mobile

According to the Global System for Mobile Communications Association (GSMA) real-time intelligence data, there are now over 10.32B mobile connections worldwide, which surpasses the current world population of 7.8B. It seems that a lot of people own more than one mobile device.

So what are we doing across those connections? According to Ericsson’s GSMA Intelligence report: The Mobile Economy 2019, over 75% of users in developed markets are reading the news – even more than are communicating over social networks. Interesting.

We are highly dependent on our mobile devices, and that’s unlikely to change. In fact, it’s going to increase if the World Advertising Research Center (WARC) is right. WARC forecasts that by 2025, 72% of all internet users will only use smartphones to access the web.

One would expect that kind of demand on our infrastructure would come at a high environmental cost. And it’s not a wrong assumption. According to the December 2019 Enablement Effect study produced in collaboration between GSMA and Carbon Trust (an independent sustainability specialist), the total annual GHG emissions of the mobile sector account for about 0.4% of total global emissions.

But mobile devices aren’t all bad. In fact, according to the joint study, mobile helped reduce over 2B tons of CO2e in 2018 across a range of categories – emission savings that were ten times greater than the global carbon footprint of the mobile industry itself.

The million-dollar question: Is digital media more sustainable than print?

Short answer, I don’t know. There’s lots of speculation, but little current data around the debate.

According to a 2011 (unfortunately, that’s the latest study we were able to find on the matter) study by the Swedish Environmental Research Institute IVL, referenced in WAN-IFRA’s 2012 Carbon Footprint of News Publishing report, from a climate change perspective:

Given that people spend 3.7 hours/day on their mobile devices and only a small percentage of that time is spent reading the news, it’s pretty clear that based on the Swedish Environmental Research Institute, digital media is better for the environment.

A 2011 Finnish study found that the carbon footprint of a single printed newspaper was ~201g, and the annual volume of daily newspapers amounted to ~75 kg of CO2e – the same as the GHG emissions of a an average car driving 450 km, or 280 miles. Noting the nearly decade-old study, we can admit that with the improved fuel efficiency of many vehicles produced today, the effective range may be a bit higher.

The largest media group in Scandinavia, Schibsted, reported in 2015 that its move to digital reduced its GHG emissions by more than 50% between 2009 and 2015.

These reports are all interesting, but, again, they’re so outdated, their accuracy and relevancy seem questionable.

However, in Schibsted’s 2018 Sustainability Report, the publisher reported that its paper consumption and printing and distribution operations accounted for 75% of its total GHG emissions. That’s pretty high and strongly suggests that digital is more sustainable than print.

Digital media distribution on a massive scale

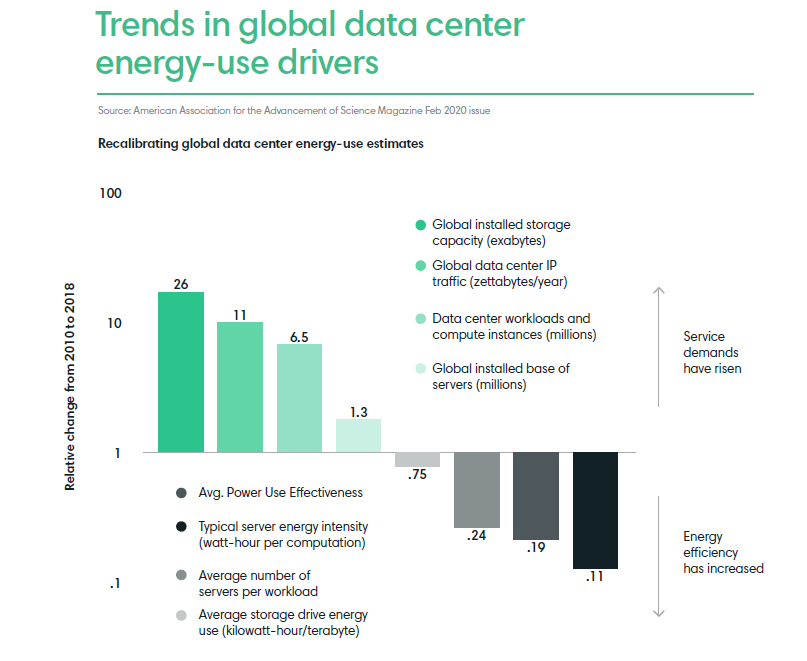

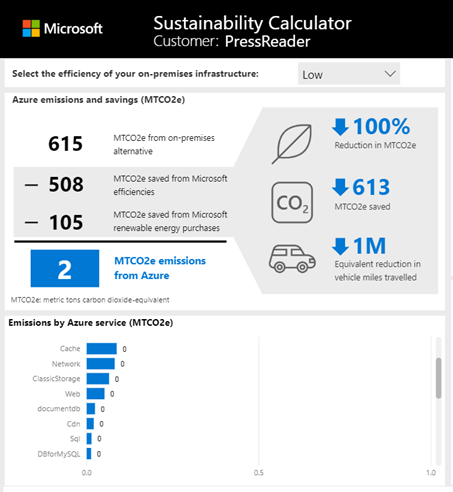

PressReader provides the largest all-you-can-read platform of newspapers and magazines where people can discover relevant and trusted content from over 7,000 newspapers and magazines from 120 countries. Processing all those publications every day is a daunting undertaking and requires serious horsepower. It’s why PressReader chose Microsoft’s Azure cloud a decade ago to handle most of the load.

As Microsoft’s sustainability calculator shows, if we were to process all those publications using in-house servers, our GHG emissions would be 615M tons CO2e a year. By using Azure, only 2M tons CO2e were emitted by the PressReader platform over the last 12 months.

Now I realize this doesn’t cover all the other environmental impacts of running our business (e.g., buildings, human resources, utilities, and travel). Still, content processing does represent a significant percentage of our overall energy consumption. It should also be noted that our Canadian head office is located in British Columbia, where over 90% of electricity is produced from renewable sources (mostly hydroelectric).

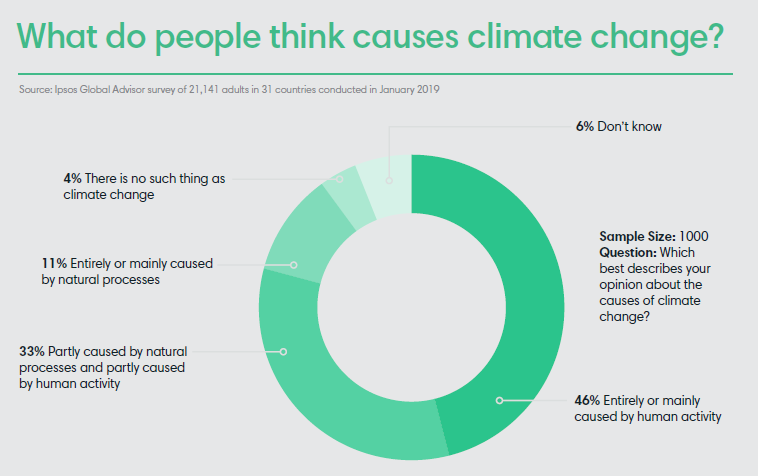

When it comes to climate change, ignorance is not bliss

It never fails to amaze me how many people still deny or disregard climate change despite a ton of publicly-available scientific research on its existence, causes, and effects.

We’re all responsible for what’s happening to our planet, so we need to practice sustainability at work and in our personal lives. We should continually learn from those who know what they’re talking about – scientists and technologists who diligently work on innovations that will create a better planet for all of us. Here are just a couple to think and learn about.

The potential of 5G

According to the Ericsson 2019 Mobility Report, by the end of 2025, 5G promises to be 100 times faster (theoretically) than our current 4G networks, generate 45% of the world’s total mobile traffic data, and connect 65% of the world’s population. Some say it will even make WiFi obsolete.

But despite assurances of its safety from many scientists including those at the International Commission on Non‐Ionizing Radiation Protection (ICNIRP) — the Germany-based scientific body that assesses the health risks of radio broadcasts — many people still believe it will cause cancer.

Others worry that our energy grids won’t be able to support 5G and that it will emit even more CO2 into the atmosphere. Some fear that our energy consumption could increase by 170% by 2026 with the rollout of 5G. The security and environmental risks that come with 5G can’t be denied, but the benefits appear to outweigh those potential threats.

Experts predict that 5G will be the first carbon-neutral network due to its energy-saving potential when coupled with IoT technology. If you look at where the most CO2 emissions come from today, 80% come from four major sectors: electricity and heat, transportation, manufacturing, and agriculture. The Information, Communication, and Technology (ITC) sector contributes about 2%.

5G + IoT can drive GHG reductions in those four sectors at a massive scale by enabling smart cities, self-driving cars, building efficiencies, improved air and water quality, emergency response and traffic control systems, smart sensors to optimize energy use, water conservation, waste reduction, and so much more.

“When it comes to applying the carbon law, the digital sector has the potential to directly reduce fossil-fuel emissions by 15% by 2030 and indirectly support a further reduction of 35% through the influence of consumer and business decisions and systems transformation.”

Johan Falk, Future Earth Stockholm Resilience Centre

Owen Gaffney, Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research et al.

2019 Exponential Roadmap

The promise of greener energy

To truly save the planet, we can’t just stop doing what we’re doing; we need to undo what we’ve done. But decarbonizing the world is a considerable challenge, and a lot of work is required to accomplish the goals established in the 2016 Paris Agreement. The first step is stopping the use of the most carbon-intensive fossil fuel – coal – and switching to lower-carbon renewable energy solutions, like wind, solar, and natural gas for our electricity.

Many efforts are already underway to decarbonize America. Most of them involve new technologies like using digital tools to transfer electricity demand to cheaper and less emissions-intensive hours of the day, reducing energy costs for consumers and improving system balancing, while also helping to reduce emissions.

And if we can get over our fear of nuclear energy, companies like General Fusion (located in Metro Vancouver, just like PressReader’s Canadian head office) could someday commercialize a safe and cost-effective nuclear-fusion-energy power plant that produces zero greenhouse gas emissions.

It will take a decade or more to get there. Still, if fusion truly is the “Holy Grail of clean power,” it could disrupt the US$8.5T energy industry and lead us to a sustainable carbon-zero economy for future generations – a future Stephen Hawking wished he could have witnessed before he passed away in 2018.

“I would like to see the development of fusion power to give an unlimited supply of clean energy and a switch to electric cars.”

Stephen Hawking

Brief Answers to the Big Questions

So would I, so would I.

Sleeping with the devil

And just to close out this debate, I would like to draw your attention to what Earth Day 2020 looked like this year.

Over the 24 hours of Earth Day, the Earth Day Network flooded the digital landscape with global conversations, calls to action, performances, video teach-ins, and more. Then they tuned into Earth Day Live from April 22 to 24 as millions of people around the world went online for a three-day mobilization to stop the climate emergency.

I understand this digital drive for saving the planet was the result of the pandemic lockdowns happening at the time. However, I still found it interesting that flooding the digital landscape with global conversations wasn’t seen to be “threatening the planet,” but just the opposite.